Who are the Druze ?

An Arab community with ancient roots and complex loyalties

5/19/20255 min read

History and Origins

The Druze are an Arab religious community that emerged in 11th-century Egypt under the Fatimid Caliphate. Their movement has its roots in Isma'ili Shiism, a branch of Shiite Islam, but soon broke away to form a distinct faith. The foundation is attributed to Hamza ibn ‘Ali, regarded as the principal architect of the doctrine. The Druze religion was initially preached publicly, but in 1043, the community closed its faith to new converts, restricting membership to those born to Druze parents.

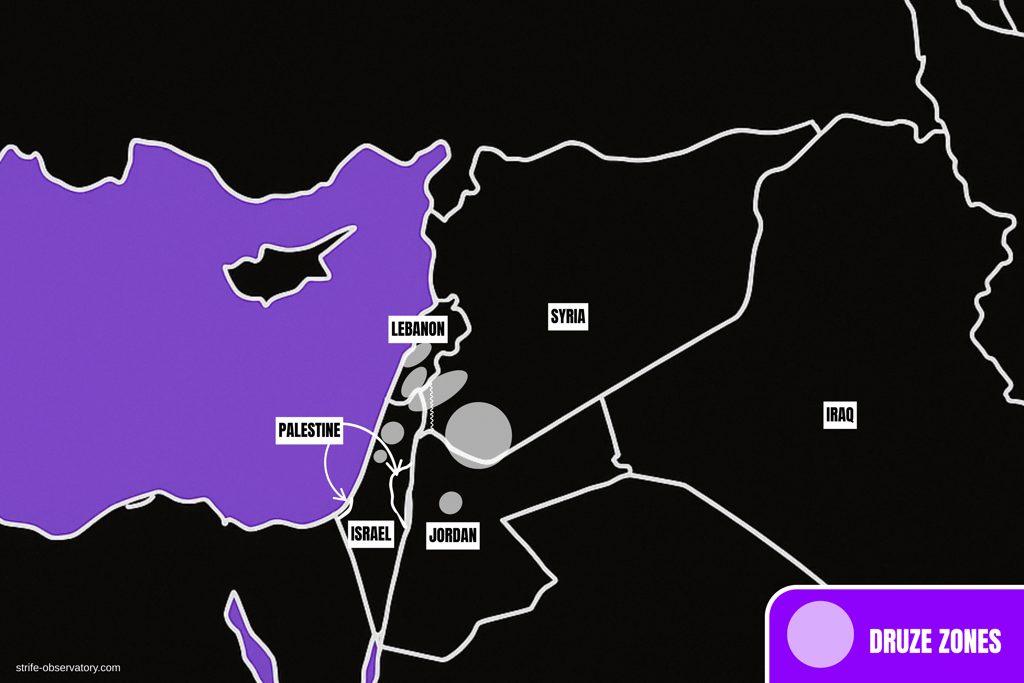

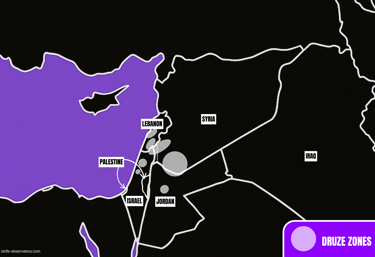

Over the centuries, the Druze migrated to the Levant, particularly to Syria (Suwayda), Lebanon, Israel, and Jordan, where they developed a strong sense of communal cohesion. Their survival often depended on prudence and the concealment of faith (taqiyya). The community also played a significant role in regional politics, most notably during Sultan al-Atrash’s revolt against France in 1925.

Beliefs and Organization

Druze faith is founded on Tawhid, a form of strict monotheism affirming the absolute oneness of God, who is invisible and beyond human understanding. God may manifest indirectly through a human image, but never directly. At the heart of Druze belief lies reincarnation (taqamuṣ) — the soul passes from one body to another exclusively within the community, with no concept of heaven or hell.

Religious practice is esoteric and discreet. Places of initiation, called khalwāt, are reserved for the ‘Uqqāl (the initiated), who have access to sacred writings known as the Books of Wisdom. The majority of Druze, known as the Juhhāl, follow the faith’s moral and social principles without direct access to these texts. Social rules are strict: marriage must be endogamous, polygamy is forbidden, and divorce is permitted. Women hold a significant place in Druze society and may also take part in initiation and religious life.

A historical loyalty to Israel

Unlike other Arab citizens of Israel, the Druze have been subject to military conscription since 1956, at their own request. This "blood alliance," sealed during the 1948 war, allowed them to gain legal recognition as a religious community in 1957, along with a separate system of religious courts.

Socially, the community is highly integrated: its high school graduation rate is the highest in the country, its army participation rate is among the strongest, and Druze women are the majority in higher education. Politically, the Druze mostly vote for Zionist parties, both right and left, and have never had their own party.

An illusion of equality

Despite this loyalty, a major turning point came with the 2018 adoption by the Knesset (Israeli parliament) of the Nation-State Basic Law. This law affirms that Israel is "the state of the Jewish people," that only this people holds the right to national self-determination, that Hebrew is the only official language, and that Jewish settlement is a "national value."

Concretely, this means:

No mention of non-Jewish minorities, including the Druze;

Arabic is no longer an official language, though it has a "special" status;

Immigration remains exclusively open to Jews, through the Law of Return;

Israeli citizenship is maintained for all, including Druze, but national belonging (in the constitutional sense) is reserved for Jews.

This de facto distinction between civil citizenship and national belonging has been perceived as a symbolic denial of the Druze sacrifices for Israel. Many community leaders, including spiritual leader Mowafaq Tarif, denounced the law as discriminatory. Political scientist Selim Brik summed up the discomfort: "The Druze have privileges, not rights."

Druze voting remains largely pragmatic, driven by local interests, often clientelist. However, a shift has been observed: in 2019-2020, nearly 20% of Druze voted for the Joint Arab List (a protest vote more than an ideological shift). Nevertheless, their electoral participation (53 to 56%) remains stable, and their parliamentary representation, although below their demographic weight, remains consistent.

The Druze of the Golan: a different case

More than 22,000 Druze live on the Golan Heights, seized by Israel during the Six-Day War in 1967 and annexed in 1981. Unlike their fellow Druze in Galilee or Mount Carmel, they have overwhelmingly refused Israeli citizenship. Attached to their Syrian identity, they have retained permanent resident status, which limits their civic rights (notably the right to vote in national elections).

In Syria, a threatened and coveted community

In Syria, the Druze represent about 3% of the population. They are mainly located in the province of Suwayda, in the Jabal al-Druze, and in the Damascus suburbs of Jaramana and Sahnaya. Historically, they have often been seen as cautious or distant from central power. However, during the Syrian civil war (2011–2024), a large part of the Druze remained loyal to the Bashar al-Assad regime more out of fear of persecution by extremist Sunni groups than ideological adherence. This relative loyalty spared them some of the reprisals suffered by other minorities.

Since the fall of the regime in December 2024, the landscape has shifted. The new president Ahmad al-Sharaa, from the former Islamist opposition and backed by Ankara, received a delegation of Druze notables in Damascus last February. In the new government formed in March 2025 and composed of 23 ministers, one Druze was appointed: Amjad Badr, who became Minister of Agriculture.

Meeting between Druze leaders and dignitaries and Ahmad al-Sharaa at the presidential palace in Damascus

To Drensions escalated in late April 2025 after the release of an audio recording attributed tuze sheikh Hikmat al-Hijri, in which he allegedly criticized the Prophet of Islam. The audio, widely circulated, sparked a wave of sectarian violence. Within a few days, 88 Druze fighters, 14 civilians, and 32 members of the Syrian security forces were killed in Suwayda, Jaramana, and Sahnaya, according to the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights.

In this highly tense context, Hikmat al-Hijri (considered the most influential spiritual leader in Syria) refused any negotiation with Damascus, which he calls an "extremist power." He calls for international intervention, accuses the state of "genocide," and receives support from the Suwayda Military Council, a coalition of 160 local militias, logistically supported by Kurdish Syrian Democratic Forces.

Following these events, the Israeli army carried out several strikes on Syrian territory, officially to protect the Druze minority. On May 3, 2025, over 20 strikes targeted military sites and strategic zones in southern Syria, including near the presidential palace in Damascus, killing one civilian. Some analysts believe that Israel is instrumentalizing this community to justify a growing military presence in the buffer zone north of the Golan, already partially occupied.

For Tel Aviv, positioning itself as the defender of the Syrian Druze is an important strategic objective, as it could justify military action and the expansion of its control zones in southern Syria. In the long term, if Syrian Druze come to request Israeli protection, it could provide a political pretext for Israel to extend its territorial hold beyond the occupied Golan.