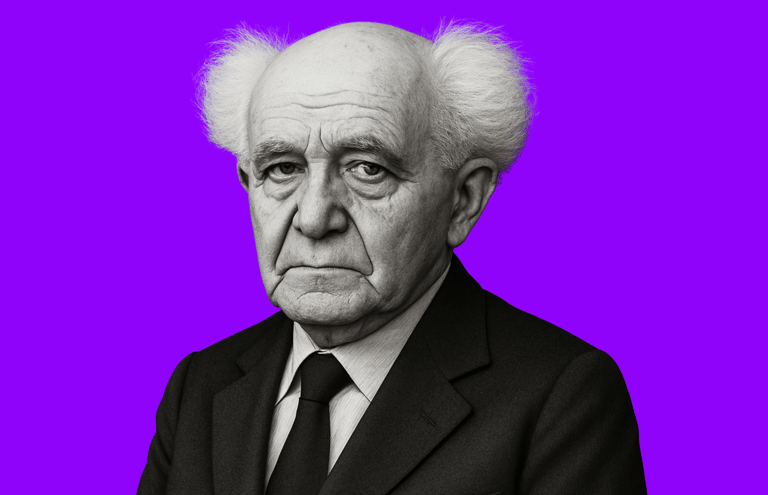

David Ben-Gurion

From Zionist Activist to Founding Father of Israel

7/12/20254 min read

Childhood and Education in a Troubled Europe

David Ben-Gurion was born on October 16, 1886, in Płońsk, in the Russian Empire (today in Poland), into a modest Orthodox Jewish family. He was one of six children of Avraham Shlomo Günzburg, a merchant and devout man committed to Jewish traditions. His childhood was marked by the anti-Jewish pogroms that swept through Eastern Europe at the end of the 19th century, creating a climate of insecurity and fear within the Jewish community.

From an early age, he developed a passion for Hebrew culture and emerging Zionist ideas, influenced by the nationalist movements spreading across Europe. He learned Hebrew and excelled as a student. In his teenage years, he joined the “Poale Zion” movement, a socialist-Zionist current that advocated the creation of a Jewish state in Palestine.

At age 20, in 1906, he emigrated alone to Ottoman-controlled Palestine, driven by the dream of building a national Jewish homeland. This decision was a bold move—leaving behind his family and country in a time of persecution, but also of new opportunity.

A Political Career in the Making

Settling first in Petah Tikva, then in Jerusalem, Ben-Gurion worked initially as a teacher and farmer. He quickly became involved in local Zionist organizations and emerged as a leading figure in the Jewish socialist movement.

He co-founded the Histadrut, the powerful federation of Jewish labor unions, and campaigned for Jewish immigration (aliyah) amid growing tensions with the local Arab population. As early as the 1920s, he adopted a firm stance on the necessity of establishing a sovereign Jewish state—if necessary, by force.

His relations with other Zionist leaders were often tense. He clashed with certain Jewish intellectuals who advocated more moderate strategies. While he collaborated with figures like Chaim Weizmann, Ben-Gurion was typically more pragmatic and authoritarian in his leadership style.

The Struggle for the Creation of Israel and Relations with Arabs

In 1935, Ben-Gurion became the executive head of the Jewish Agency, the official representative body of the Jewish people before the British authorities. He played a central role in planning and organizing what would become the State of Israel.

However, the Zionist project also involved violent confrontation. Ben-Gurion adopted a position that can be described as colonial in nature—viewing Palestine as a land to be conquered and developed, often at the expense of the native Palestinian population. He made controversial statements, at times justifying Arab dispossession and accepting violence as a legitimate tool to secure Jewish interests.

He worked closely with British officials but also led resistance efforts during the Palestinian Arab revolts of the 1930s. His public and private statements reveal a worldview in which the survival and growth of the Jewish community took precedence over Arab rights—laying the foundation for a conflict that continues to this day.

Proclamation of the State of Israel

On May 14, 1948, David Ben-Gurion officially proclaimed the creation of the State of Israel, amid escalating tensions with Arab populations in Palestine and neighboring states. The declaration came as the end of the British Mandate plunged the region into civil war, and a coalition of Arab countries immediately declared war on Israel.

As both Prime Minister and Minister of Defense, Ben-Gurion played a direct, central, and decisive role in the 1948 war—referred to by Israelis as the War of Independence, and by Palestinians as the Nakba (“The Catastrophe”).

David and Golda, 1956

“If I were an Arab leader, I would never make peace with Israel. That’s natural: we have taken their country. God may have promised it to us, but what does that matter to them? Our God is not theirs. There has been anti-Semitism, the Nazis, Hitler, Auschwitz—but was that their fault?”

David Ben-Gurion, quoted by Nahum Goldmann in The Jewish Paradox

The 1948 War

During this conflict, Israeli forces conducted coordinated military operations that led to the massive depopulation of over 400 to 500 Palestinian villages and the exodus of 700,000 to 750,000 Palestinians. This process has been documented by numerous historians, including Israeli scholar Ilan Pappé, who explicitly describes it as “ethnic cleansing” in his book The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine (2006).

Ben-Gurion actively supported and organized these expulsions, particularly through Plan Dalet (Tochnit Dalet), a military directive aimed at seizing control of territories allocated to Israel by the UN partition plan—as well as key Arab areas. The plan authorized the destruction of villages, the expulsion of Arab populations, and the confiscation of their land.

By 1949, fewer than 150,000 Palestinians remained in what became Israel—down from nearly one million before the war—representing a demographic disappearance of over 80% of the Arab population within the new state's borders.

Legacy, Final Years, and Contested Record

Among the political figures he helped promote, Ben-Gurion played a key role in the rise of Golda Meir, appointing her Minister of Labor, then Foreign Affairs. She would later become Prime Minister in 1969, years after his final retirement. In 1954, Ben-Gurion temporarily stepped down as Prime Minister “to rest” but remained highly influential. He handed over leadership to Moshe Sharett while continuing to monitor state affairs closely. In 1955, he returned to power and remained Prime Minister until 1963, when he handed the reins to Levi Eshkol.

After leaving the premiership, Ben-Gurion stayed active as a Knesset member for a few more years before retiring completely from political life in 1970. He withdrew to the Sde Boker kibbutz in the Negev desert—a region he tirelessly promoted for Jewish settlement. He died there on December 1, 1973, shortly after the Yom Kippur War.

Ben-Gurion’s legacy is immense for Israelis: he is revered as the founding father of the state, a visionary strategist, and a tireless institution builder. Yet his record remains deeply controversial—particularly due to his role in the forced displacement of hundreds of thousands of Palestinians in 1948 and the policies he pursued toward Arab populations.